Understanding the two principles – which are separate but related – is best started by looking at the tonal structure of the classical organ.

Extension

The extension principle enables a number of stops of like tone but different pitch to be provided from one single, enlarged rank of pipes.

In a conventional classical organ, each manual controls its own ‘department’ of stops, for example on a simple organ with two families of tone on one manual;

8′ Diapason

4′ Principal

2′ Fifteenth

8′ Flute

4′ Piccolo.

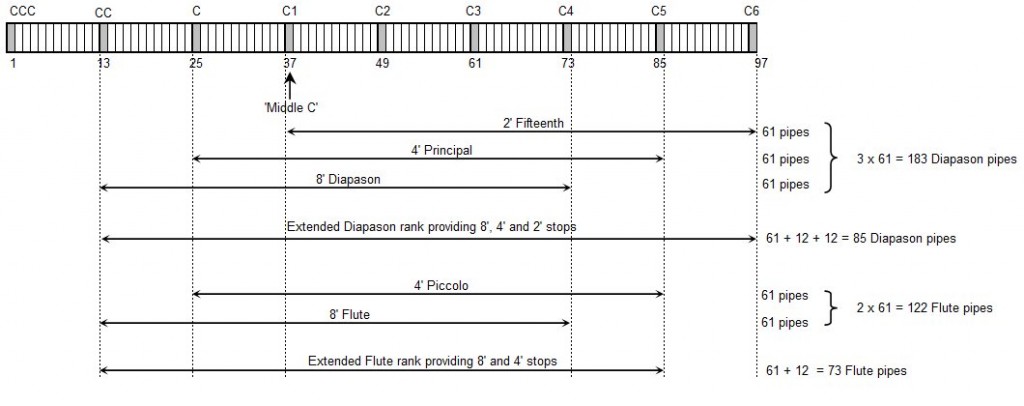

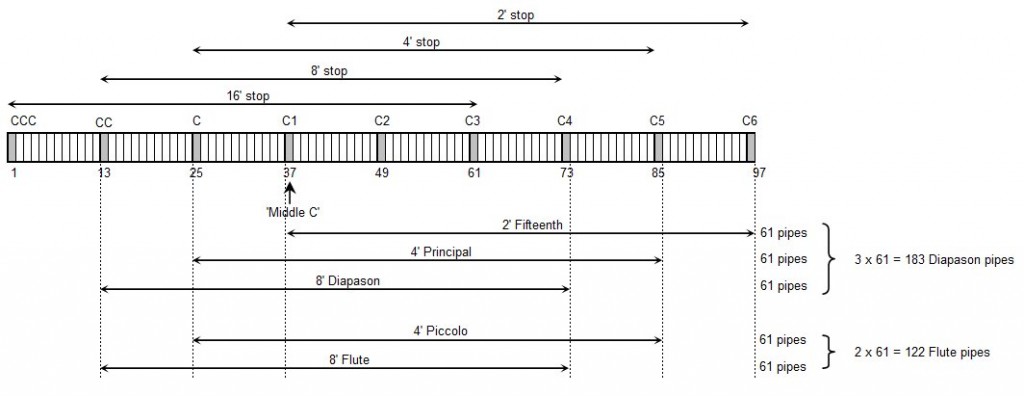

Each of these five stops is equipped with 61 pipes (for a standard 5-octave manual compass). Three of the stops are of Diapason tone (Diapason, Principal and Fifteenth) and two of the stops are of Flute tone (Flute and Piccolo). The following diagram (fig 1) shows the relation between the 5 different stops and the compass (range of notes) of the instrument. The 16′ octave is shown but is not used in this example.

It will be seen that the three Diapason stops of 61 pipes require a total of 183 pipes, and the two Flute stops of 61 pipes require a total of 122 pipes. It will also be seen that there is considerable overlap between the three Diapason and two Flute stops.

The extension principle eliminates this overlap by combining the three Diapason stops, reducing the number of pipes required from 183 to 85, and similarly reducing the pipes required for the two Flute stops from 122 to 73 (fig 2).

To do so however requires a complex electric (or nowadays electronic) relay. On large theatre organs these become very large and complex and are one of the most significant parts of the instrument.

As usual however, one does not get something for nothing and the main disavantage of the extension principle is that the stops, even if of a like family, are no longer independent of each other. The tonal structure of the classical organ is based on families of like tone at different pitches which when played together create a chorus of sound, for example a diapason chorus, a flute chorus or a reed chorus. The skill of the organbuilder in determining the relative strength and scaling of different stops is key to achieving a satisfactory chorus, and of course when all the stops in a chorus come from the same set (rank) of pipes, then it is impossible to exercise this skill.

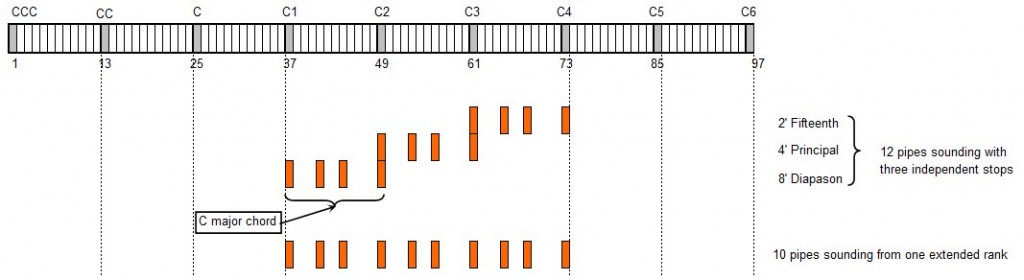

A further – and at first glance rather technical problem – concerns mutation stops, e.g. 2 2/3 (twelfth) or 1 3/5 (tierce) stops derived from a rank of pipes using the extension principle (see entry under Pitch). These stops are, conventionally, tuned a perfect third or fifth from the unison; however because of the equal temperament scale most modern organs are tuned to, these intervals on derived mutations are not perfect but tempered since the pipes used for the mutation stops also serve the unison stops as well. Such derived mutation stops therefore lack the effectiveness of those on ‘straight’ organs and, to expert ears, sound ‘wrong’. Yet another problem is that an extension chorus (if that is not a contradiction in terms!) plays fewer notes than an chorus from unextended stops, the so-called ‘missing note’ effect. The diagram below (fig 3) explains this, taking the example of a C major chord with three stops – 8′, 4′ and 2′ -drawn from the same family.

Nonetheless, some organ builders developed a high level of skill in overcoming these shortcomings. Notable in this was John Compton, who created – with great care and selectiveness in the scaling and voicing of pipework – some very fine classical organs in which the extension principle was used. The remarkable organ at Downside Abbey is a case in point, where a certain few extended ranks provide a number of stops alongside other non-extended stops.

Why is the extension principle considered acceptable for the theatre organ? Purists from a classical organ persuasion might argue otherwise, but their case usually – and debatably – hinges around the concept that the tonal structure of the theatre organ depends only on the development of the chorus. The unit theatre organ (or ‘Unit Orchestra’, to use Hope-Jones’ term) depends more on the mixing of different – sometimes extreme – tone colours to create an ensemble of solo or accompanimental sounds. Although some regard the theatre organ as an imitative instrument, many successful instruments have few truly imitative stops. The power (or foundation) of the theatre organ ensemble depends primarily on the Tibia, bolstered by other harmonically neutral stops such as the diaphonic diapason and rounder Tuba stops. Harmonics and tonal variety are provided by narrower scaled stops such as the orchestral or colour reeds (vox humana, oboe, saxophone, kinura) and strings. Derived stops at higher pitches (4′ and 2′) add to this effect, but it is noticeable that the treble pipes in such extended ranks are regulated relatively softly, compared to similar stops on a ‘straight’ classical organ where the treble pipes of an unextended string stop may remain as bright and bold as those in the middle of the stop.

Unification

Unification takes the extension principle a stage further, by allowing stops to be playable from different manuals.

Take an example of the stops on a “small” organ specification with two manuals and pedals, and one tone colour (Flute)

Pedal (32 notes) Accompaniment (61 notes) Solo (61 notes)

16′ Bourdon

8′ Flute 8′ Flute 8′ Flute

4′ Flute 4′ Flute

2′ Flute

If all the stops were independent then there would be 2 x 32 note pedal stops (so 64 pipes), 2 x 61 notes Accompaniment stops (so 122 pipes) and 3 x 61 note Solo stops (so 183 pipes) giving a total of 64 +122 +183 = 369 pipes.

Applying the extension principle would give us three extended ranks; a Pedal extended flute rank of 32 + 12 = 44 notes, an Accompaniment extended flute rank of 61 + 12 = 73 notes and a Solo extended Flute rank of 61 + 12 +12 = 85 notes, altogether giving 192 pipes. However (for example) the 8′ Flute on the Solo, Accompaniment and Pedal would each play their own set of pipes, although the notes would be similar.

In this example of unification, the 8′ Flute on the Accompaniment and the 8′ Flute on the Solo would play the same identical pipes from a single rank. To cover the entire specification in this example in such a way, there would need to be only one single rank of Flute pipes, extended to cover the range of notes from the bottom of the Pedal 16′ Bourdon (CCC) to the top of the Solo 2′ Flute (C6). Such a rank would then contain 12 + 61 + 12 + 12 = 97 pipes. Making an extended rank available over several manuals like this is referred to as ‘unification’ and the rank of pipes sometimes referred to as a ‘unit’.

Unification and extension requires that the organ relay has completely independent control over each pipe, regardless of the stops drawn or the notes played. This has implications on the design of the windchest on which the pipes sit.

On a conventional classical organ, the stops are laid out on a soundboard which contains a pallet (the valve that, indirectly, admits air to the pipe) for each note of the windchest. A slider (a strip of wood or other stable material) runs the length of the soundboard, between the pipes and the pallet, and is moved when a stop is drawn at the console so that holes in the slider allow air from the pallet to reach a particular pipe. Thus, when a note is played and a stop is drawn, the pipe sounds. Mechanical considerations make it practically impossible – without resort to specific devices – to apply the unit principle to such a soundboard.

On a unit organ, the pallet / slider function is replaced by the organ relay, and the logic implicit in the relay wiring and configuration. Each pipe has its own pallet and can, via the relay, be played from any combination of stop and note.

See further: